November Newsletter Topics

ACCESSIBILITY FYI — UFAS Door Maneuvering Space

Large drain line located within the maneuvering clearance of an entry door.

Since the earliest edition of UFAS in 1984, maneuvering spaces at doors have required a clear, unobstructed floor area. This rule predates the Fair Housing Act, predates ANSI updates, and continues through today’s accessibility standards. Despite this, obstructions placed directly within required clearance, especially on the latch side, remain one of the most common issues we encounter during plan reviews and field inspections.

The reasoning behind the requirement has never changed. Door usability depends on a wheelchair user’s ability to position, pull, and clear the door's swing path. If a post, pipe, riser, or other fixed object occupies that space, the door can’t function as intended. This isn’t interpretation; it’s mechanics.

These requirements apply at public entrances, common-use doors, and at the entries to covered dwelling units. The rule is the same: if the space is required for approach or maneuvering, it must remain clear.

RAS CORNER — The Toilet Height Problem

Elevated toilet seat used to try and meet seat height requirements.

Every field visit produces at least one moment that makes the team pause. This month it came from a toilet that had been lifted well past what anyone would consider reasonable. The goal was simple. Make the height work without replacing the fixture. The question became obvious. How high can we go before the fix becomes part of the problem?

Toilet height has a defined range for a reason. Transfers matter. Grab bar positions matter. User stability matters. Once the height climbs too far, the “solution” starts creating new issues faster than it solves the old ones.

Sometimes a simple adjustment works. Other times, the only real answer is a new fixture. This particular photo reminded us how far some installations try to push that line and how important it is to know where the limit actually is.

PROJECT HIGHLIGHT — Corrections Facility Assessment

Interior view of a corrections housing unit with cells and stairs.

This month, our team was asked to assess accessibility conditions inside a corrections facility. Secure environments often create unique challenges because circulation, operations, and user groups differ from those of typical commercial or residential sites. Even so, the baseline requirements for usability still apply.

During the assessment, we reviewed dayrooms, circulation paths, restroom facilities, and areas used for visitation. Many of the issues we observed were the result of incremental modifications made over time or original construction that did not account for accessibility. The setting was different, but the fundamentals remained the same. Doors must be usable, routes must be navigable, and fixtures must support independent access.

These reviews reinforce that accessibility is not dependent on occupancy type. Whether a space serves residents, staff, visitors, or a secure population, the principles remain consistent. People must be able to use the environment safely and independently.

Public vs. Not Public: A Practical Interpretation of “Public and Common Use” in Fair Housing Compliance

A professional perspective shaped by years of reviewing and inspecting Fair Housing Act projects

Multifamily housing development under construction with multiple three- and four-story residential buildings overlooking a retention pond.

When people talk about Fair Housing Act compliance, they often jump straight to the seven technical requirements inside covered dwelling units. While those requirements matter, many projects run into challenges long before anyone measures a threshold or checks a bathroom layout. One of the most overlooked and often misunderstood parts of Fair Housing Review happens at the very beginning: understanding what the FHA means by public use, common use, and private residential space.

This blog reflects how I approach these classifications in the field during Fair Housing inspections and plan reviews, and it also reflects the consistent method we use at ACI. Because the FHA is not written like a prescriptive building code, interpretation is part of the process. In my experience, getting the interpretation right early is one of the most effective ways to reduce risk and avoid costly corrections.

Why This Distinction Exists in Fair Housing Accessibility

The FHA’s design and construction requirements are intended to ensure equal access for people with disabilities across multifamily housing. The Fair Housing Design Manual organizes the built environment into three major categories:

Public use areas

Common use areas

Private dwelling units, where five of the seven FHA design requirements apply

These terms appear straightforward, but in practice, they are some of the most frequently misunderstood parts of any Fair Housing Review. Misinterpretation often begins when teams rely on everyday definitions instead of FHA intent.

Clarity at the outset prevents many of the disputes and redesigns I see later in development.

ACI’s Interpretation of What the FHA Design Manual Intends

The Design Manual uses “public and common use” repeatedly, but it does not always define them with real-world clarity. Below is the approach that consistently proves reliable during our Fair Housing inspections and reviews.

Close-up of a restroom sign labeled ‘104 Restrooms’ with tactile characters and Braille, mounted on a white wall near an interior door.

Public Use Areas

Public use areas are spaces where members of the public may enter while interacting with the property. Frequency does not matter. Restricted access does not matter. A gate, keypad, or appointment system does not change the classification.

If prospects or members of the public are expected to enter the space, it is public use.

Examples include:

Leasing offices

Model units

Public paths leading to leasing

Visitor parking

Any entrance used by prospects or tours

Teams often assume that a gated community is “not public.” The FHA focuses on expected interaction, not how a door is locked.

Outdoor common-use grilling station at a multifamily community. Features built-in grills, sinks, counters, overhead lighting, and rubber mats along the walkway.

Common Use Areas

Common use areas are shared by residents. If more than one resident uses the space, it is common use. Controlled access does not alter the category.

Common examples include:

Mail centers

Trash rooms

Clubhouses

Fitness centers

Pools

Amenity paths

Resident parking

A frequent mistake is assuming that “shared, but controlled access” equals private. The FHA does not interpret it that way. Function always determines classification.

Private Residential Areas

Private residential areas are the spaces intended for the use of a single resident. These areas are not classified as public use or common use. Examples include private garages, individual patios, and private storage rooms.

Private dwelling units themselves are subject to five FHA design requirements, including:

Interior accessible route

Door usability

Reach ranges

Bathroom reinforcement

Usable kitchens and bathrooms

Exterior private spaces like patios do not need to be accessible, but the route inside the dwelling unit leading to them must comply.

This nuance is often missed in both design reviews and Fair Housing inspections.

Where Misinterpretation Happens Most Often

Multifamily development site plan marked with red circles and arrows.

Across hundreds of Fair Housing reviews, the same issues appear repeatedly. These stem from applying everyday logic to terms that have very specific meanings under the FHA.

Leasing Office Entrances

If an entrance is used by prospects or residents, it must be treated as accessible. Intent is irrelevant if actual use differs.

Inside the Leasing Office

Even when the leasing office is not inside a covered multifamily building, the public areas within it remain subject to accessibility expectations. This includes:

Lobbies

Conference rooms

Public restrooms

Any service area used by prospects

Mail Centers

Mail centers are always common use, even when located in standalone kiosks or small buildings. Reach ranges and clear floor spaces must be included in Fair Housing design.

Parking Areas

Misclassification here is common:

Visitor parking = public use

Resident parking = common use

Failing to designate public-use parking near leasing areas is a frequent Fair Housing Review finding.

Pools and Clubhouses

If residents share it, it is common use.

If prospects are shown the space, it is temporarily public use.

Either way, accessibility applies.

Amenity Paths and Outdoor Features

Dog parks, trails, grilling stations, and outdoor fitness equipment all fall under common use when shared by residents.

Private Patios and Balconies

The balcony itself is private.

The interior route to it must still comply with FHA design requirements.

Corridors and Breezeways

These are common use circulation paths. Accessible route requirements apply throughout.

Trash Rooms and Package Rooms

Shared = common use

Monitored or access-controlled does not make them private.

Why Accurate Classification Matters

Getting public, common, and private classifications right at the beginning of a Fair Housing Review makes the rest of the project more predictable and reduces costly changes later.

Testers Focus on Public Use Areas First

Testing activity typically begins at:

Leasing paths

Public-use parking

Entrances

Model units

Routes used on tours

If these areas were misclassified during design, the project becomes immediately vulnerable to a complaint.

Corrections Are Expensive After Construction

Typical corrections resulting from misclassification include:

Regrading sidewalks

Reconfiguring parking or mail centers

Adjusting slopes at entrances

Installing new accessible routes

Rebuilding landings

Exterior work is especially costly due to its connection to grades, drainage, and elevations.

Lenders and Buyers Are Increasing Accessibility Scrutiny

Fair Housing compliance is now a common part of:

Acquisitions

Refinancing

Equity reviews

Property condition assessments

Correct classifications early protect owners during due diligence.

Design Teams Depend on Accurate Classification

Civil, architectural, MEP, and landscape teams all rely on these initial determinations. Misclassification leads to conflicting drawings, incorrect slopes, and missing accessible routes.

Contractors Build What Is Shown

Contractors build what is detailed in the drawings. If a space is misclassified on the plans, the constructed condition will reflect that same assumption. Contractors cannot be expected to infer accessibility requirements that were never documented

The Owner Retains Long-Term Exposure

Even after occupancy, classification errors can surface through:

Complaints

Testing

Renovations

Refinancing

Management transitions

Correct classification from day one reduces long-term operational risk.

How We Approach It at ACI

At ACI, our Fair Housing reviews focus on clarity, defensible interpretation, and the real-world use of the property. Rather than treating FHA terminology as abstract, we evaluate each space based on expected function.

Function Determines Classification

Prospects use the space = public use

Residents share it = common use

One resident uses it = private

Real-World Use Matters More Than Notes on a Sheet

If residents or staff use a route differently than intended in the drawings, FHA interpretation follows actual use.

The Five Internal FHA Requirements Are Non-Negotiable

We evaluate every covered unit for:

Door usability

Accessible route

Reach ranges

Bathroom reinforcement

Usable kitchen and bathroom layouts

We Review Drawings as a Connected System

We examine:

Elevations

Slopes

Parking relationships

Walks

Amenity access

Building entries

FHA issues appear where disciplines intersect.

We Favor Conservative, Defensible Interpretation

If a space could reasonably be public or common use, we treat it accordingly.

Our Process Focuses on Long-Term Risk Management

We evaluate how decisions today will perform:

During construction

During occupancy

During testing

During resale or refinancing

Durability matters.

Final Thoughts

Understanding how the FHA classifies public use, common use, and private residential areas is one of the foundational steps in Fair Housing compliance. These distinctions guide how routes are planned, how amenities are accessed, and how teams coordinate across disciplines.

Most confusion does not come from bad design. It comes from reasonable assumptions that do not match how the FHA Design Manual defines space. With consistent interpretation and clarity at the start, teams reduce risk and achieve smoother outcomes during construction, inspections, and occupancy.

If your team needs assistance interpreting these classifications or aligning design decisions with Fair Housing accessibility requirements, ACI is available to help.

Clear classifications lead to better coordination, fewer surprises, and a more efficient path through Fair Housing compliance.

Disclaimer: This content is for general informational purposes only and does not constitute legal or regulatory advice. Accessibility requirements vary by jurisdiction. Always consult federal, state, and local regulations and licensed professionals to ensure compliance.

Why is it Important for a Company to Remain ADA Compliant?

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) sets the benchmark for ensuring that all individuals, regardless of their physical abilities, can access and benefit from the services and facilities that companies provide. Understanding and adhering to ADA compliance not only fulfills a legal obligation but also promotes a culture of inclusivity and equal opportunity.

In today’s increasingly inclusive society, it is imperative for businesses to prioritize accessibility.

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) sets the benchmark for ensuring that all individuals, regardless of their physical abilities, can access and benefit from the services and facilities that companies provide. Understanding and adhering to ADA compliance not only fulfills a legal obligation but also promotes a culture of inclusivity and equal opportunity.

In this article, we will delve into the importance of maintaining ADA compliance, the role of Registered Accessibility Specialists, and the intricacies of accessibility standards, including Texas Accessibility Standards.

Understanding ADA Compliance Legal Mandates and Implications

The ADA, enacted in 1990, is a comprehensive civil rights law that prohibits discrimination against individuals with disabilities. For businesses, compliance is not merely a suggestion but a legal requirement. Failure to comply can result in severe penalties, including fines and potential lawsuits. ADA compliance for companies ensures that facilities are accessible, communications are effective, and employment practices are equitable.

Promoting Inclusivity and Diversity

Beyond legalities, ADA compliance represents a commitment to inclusivity and diversity. By fostering an environment that accommodates individuals with disabilities, companies not only broaden their customer base but also attract a diverse workforce. This inclusiveness enhances the company’s reputation and can lead to increased employee satisfaction and customer loyalty.

The Role of Registered Accessibility Specialists

Registered Accessibility Specialists play a crucial role in guiding companies through the complexities of ADA compliance. These experts are well-versed in accessibility standards and can provide invaluable insights and recommendations.

Comprehensive Accessibility Audits

Accessibility audits are a critical first step in achieving ADA compliance. Registered Accessibility Specialists conduct thorough evaluations of company facilities, identifying areas that require modifications to meet accessibility standards. These audits provide a roadmap for necessary improvements, ensuring that companies adhere to legal requirements and foster an inclusive environment.

Continuous Education and Training

Accessibility standards are continually evolving, and staying informed is essential. Registered Accessibility Specialists offer training programs to educate company personnel on the latest accessibility requirements and best practices. This ongoing education empowers companies to maintain compliance and adapt to new standards as they arise.

Navigating Accessibility Standards - Federal and State Standards

While the ADA and Federal Access Board set the federal standard (Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) Accessibility Guidelines), individual states may adopt their own standards. Texas, for instance, has established the Texas Accessibility Standards (TAS), which align closely with the federal guidelines but include state-specific provisions. Understanding these nuances is vital for companies operating across different jurisdictions.

Implementing Accessibility Features

Meeting accessibility standards often involves implementing physical modifications. For facilities, this may include installing ramps, accessible restrooms, and appropriate signage. For updated information on the changing landscape of accessibility standards, please refer to our page “Breaking Barriers – The ACI Access Journal”.

The Business Case for ADA Compliance – Enhancing Customer Experience

ADA compliance directly impacts customer experience. By ensuring that facilities and services are accessible, companies can cater to a broader audience. This commitment to accessibility not only improves customer satisfaction but also opens new market opportunities.

Mitigating Legal and Financial Risks

Non-compliance with ADA standards can lead to costly legal battles and damage to a company’s reputation. Proactively addressing accessibility issues through compliance efforts reduces the risk of litigation and associated financial penalties.

Driving Innovation and Growth

Embracing accessibility can spur innovation. By addressing the needs of individuals with disabilities, companies may discover new opportunities for product development and service enhancement. This innovative approach can differentiate a company from its competitors and drive long-term growth.

Conclusion

In summary, maintaining ADA compliance is both a legal necessity and a moral imperative for companies. Our team of Registered Accessibility Specialists is here to guide you through each phase, ensuring your project meets or exceeds these standards from the initial planning stages through final inspection. We pride ourselves on being “the architect’s architect.” Dedicated to promoting inclusive design and protecting your project from compliance issues down the line.

Visit www.acico.com to learn more about our services and how we can help you create compliant, inclusive, and inviting spaces.

Disclaimer: This post is for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal or regulatory advice. Code interpretations may vary by jurisdiction and project. Always consult a Registered Accessibility Specialist (RAS), certified code official, or legal counsel familiar with the applicable standards in your area before making design or compliance decisions.

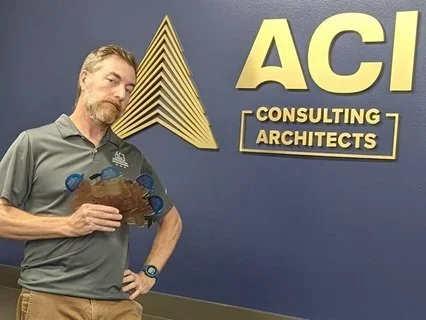

From Investigations to Insight: The Evolution of ACI

ACI was founded by Henry Hermis and Jack McGinty, whose combined expertise helped shape the firm’s early reputation for technical accuracy and investigative detail. Together, they set out to provide reliable, expert-driven evaluations of construction practices, launching a company built on forensic investigations, code compliance consulting, and a deep understanding of the built environment.

Our Origins: ACI – American Construction Investigations

Every company has a story. Ours began in 1994, with a name that reflected our original mission: ACI – American Construction Investigations.

ACI was founded by Henry Hermis and Jack McGinty, whose combined expertise helped shape the firm’s early reputation for technical accuracy and investigative detail. Together, they set out to provide reliable, expert-driven evaluations of construction practices, launching a company built on forensic investigations, code compliance consulting, and a deep understanding of the built environment.

The foundation of accessibility consulting started here.

A Shift Toward Accessibility

As the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) began reshaping how spaces were designed and built, ACI recognized an emerging need in the industry: accessibility compliance wasn’t just about meeting regulatory standards. It was about promoting equity, managing risk, and protecting the long-term value of the built environment.

In response, ACI expanded its services to include third-party accessibility reviews and field inspections for compliance with the Texas Accessibility Standards (TAS). With a growing team of Registered Accessibility Specialists (RASs), ACI became a go-to provider for TAS plan reviews and inspections, helping clients navigate state-mandated requirements with precision and clarity—something we proudly continue to offer today.

Through it all, Henry remained the cornerstone of ACI’s values, fostering a company culture rooted in accountability, humility, and a deep sense of family and mentorship.

Expanding Services and National Reach

In the early 2000s, Jeromy Murphy returned to ACI in a managing role, bringing both technical expertise and a natural leadership style that complemented Henry’s vision. During this period, ACI began to broaden its scope, adding Fair Housing Act (FHA) design guideline consulting to its growing list of accessibility services. This expansion positioned ACI as a key resource for architects and developers seeking clarity and Fair Housing Act design compliance, particularly in the multifamily residential market.

Throughout the mid-2000s and into the 2010s, ACI strengthened its national footprint, becoming a trusted partner to some of the nation’s leading multifamily developers, architects, and legal teams. Our expert consulting services helped project teams proactively meet ADA and multifamily accessibility compliance requirements during design and construction. While our accessibility litigation support work is primarily defense-oriented, ACI has also been called upon by U.S. Attorneys as subject matter experts in accessibility investigations, reinforcing our credibility and neutrality in high-stakes, compliance-driven environments.

ACI has worked in over 30 states nationwide, bringing accessibility expertise coast to coast.

When Henry Hermis passed away in 2020, Jeromy—by then a partial owner and one of ACI’s most tenured employees—stepped into full leadership. Under his direction, the firm rebranded from ACI – American Construction Investigations to ACI Consulting Architects, a name that better reflected its evolving identity and nationwide focus. Jeromy’s steady guidance helped ACI maintain its values while embracing the next chapter of growth.

A New Ownership Model with Familiar Faces

ACI’s leadership today: built on legacy, driven by purpose.

In 2024, ACI completed a strategic transition to a six-partner ownership model, reflecting the company’s continued growth and long-standing commitment to developing leadership from within. While ownership is now shared, day-to-day direction remains firmly rooted in a core executive team with deep institutional knowledge and complementary strengths.

Among the partners are Victoria Popoca, who began her ACI journey in 2005 as an administrative assistant and now serves as Director of Human Resources, and Robert Green, a longtime consultant and strategist in accessibility compliance whose insight has helped shape ACI’s national reach and service delivery. Together with Jeromy Murphy, whose leadership carried the firm through its most pivotal chapter, they form the foundation of ACI’s current leadership.

The transition to shared ownership marked more than a structural change—it ensured long-term stability while honoring the firm’s legacy of mentorship, accountability, and technical excellence.

Looking Ahead

At ACI, we’re more than consultants—we’re a team, a family, and a legacy in motion.

From its origins as ACI – American Construction Investigations to its current role as a national leader in accessibility and code consulting, ACI has remained grounded in the principles that launched it over 30 years ago: technical excellence, integrity, and a deep understanding of how the built environment affects real lives. While the regulations and challenges have evolved, our mission has stayed the same, to help our clients navigate compliance with clarity, confidence, and purpose.

As we look to the future, we remain committed to the idea that accessibility isn’t just a legal requirement—it’s a fundamental component of responsible design, thoughtful development, and long-term success.

Work With Us

Whether you need a TAS plan review, accessibility inspection, or expert guidance for your multifamily development, ACI is here to help.

Contact us today to learn how our team of Registered Accessibility Specialists and consultants can support your next project with insight, precision, and over 30 years of experience.

The Role of a Registered Accessibility Specialist and Why They Matter to Your Business

Ensuring your business is accessible to everyone is not just a legal requirement—it’s also a smart business move. Across the United States, accessibility consultants help businesses navigate federal, state, and local requirements for accessible design and construction.

In Texas, this role includes the specialized services of a Registered Accessibility Specialist, who is licensed to conduct the Texas Accessibility Standards (TAS) plan reviews and inspections required by state law. Whether your project is in Texas or elsewhere in the country, working with an experienced accessibility consultant can help you avoid costly construction changes, reduce the risk of delays, and ensure your facility is welcoming to all individuals, including those with disabilities.

Ensuring your business is accessible to everyone is not just a legal requirement—it’s also a smart business move. Across the United States, accessibility consultants help businesses navigate federal, state, and local requirements for accessible design and construction.

In Texas, this role includes the specialized services of a Registered Accessibility Specialist, who is licensed to conduct the Texas Accessibility Standards (TAS) plan reviews and inspections required by state law. Whether your project is in Texas or elsewhere in the country, working with an experienced accessibility consultant can help you avoid costly construction changes, reduce the risk of delays, and ensure your facility is welcoming to all individuals, including those with disabilities.

What Is a Registered Accessibility Specialist?

A Registered Accessibility Specialist is certified to evaluate building plans and completed projects for compliance with accessibility standards. In Texas, this includes performing the mandatory TAS plan review before construction and conducting the on-site inspection after substantial completion.

Outside Texas, accessibility consultants perform similar services—reviewing plans, inspecting completed work, and advising on accessibility compliance under applicable state or local codes as well as federal laws like the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and the Fair Housing Act (FHA).

Typical services from a Registered Accessibility Specialist or accessibility consultant include:

Reviewing construction documents for compliance with accessibility requirements

Conducting on-site inspections to verify compliance

Advising design teams on compliant, functional solutions

Helping owners resolve accessibility issues efficiently and cost-effectively

Why Accessibility Compliance Matters

Meeting accessibility standards is more than just following the law—it demonstrates a commitment to inclusivity and equal access. Benefits of compliance include:

Avoiding legal penalties from state or federal agencies

Protecting reputation by serving all members of your community

Reducing costs by catching issues before they’re built

Expanding your customer base by ensuring full accessibility

The Value of Early Involvement

Whether you are in Texas working with a Registered Accessibility Specialist under TAS requirements, or in another state working with an accessibility consultant, engaging them early in the design process can:

Identify potential compliance concerns before permitting

Streamline project timelines by reducing rework

Ensure compliance is integrated seamlessly with the design vision

ACI works with clients nationwide to integrate accessibility compliance into every stage of their project. From preliminary design guidance to final inspections, we partner with your team to deliver compliant and functional spaces anywhere in the U.S.

Choosing the Right Accessibility Partner

When selecting a Registered Accessibility Specialist or accessibility consultant, consider the following:

Proper certification or licensing for your jurisdiction

Experience with your building type or occupancy

A track record of clear, solution-oriented communication

Up-to-date knowledge of current accessibility standards

Conclusion: Compliance That Works for You

Accessibility is both a legal and ethical priority. A skilled Registered Accessibility Specialist or accessibility consultant ensures your project complies with all applicable standards—state, federal, or both—while keeping your project on track.

ACI provides TAS plan reviews and inspections in Texas and full accessibility consulting, ADA compliance, and Fair Housing compliance services nationwide. Whether your project is in Houston or Honolulu, our team has the expertise to guide it from design through completion with accessibility compliance built in.

The Straight Path Less Followed

I was certain that I was going to be the next famous architect.

When I was about eight years old, my church in Port Arthur, TX, started construction on a new sanctuary. In the moments before, between and after church, I would sneak into the construction site and explore the ever-evolving space. My father was quite a talker so his after church coffee routine afforded me plenty of time to disappear into the architecture.

By Jeromy Grant Murphy, AIA, RAS, ICC

I was certain that I was going to be the next famous architect.

When I was about eight years old, my church in Port Arthur, TX, started construction on a new sanctuary. In the moments before, between and after church, I would sneak into the construction site and explore the ever-evolving space. My father was quite a talker so his after church coffee routine afforded me plenty of time to disappear into the architecture.

The sanctuary was a contemporary design but with proper and orderly Presbyterian restraint. The soaring PLAM trusses rested upon tan bricks. The floors were practical slaughter-house tile selected primarily because spilt communion grape juice wouldn’t leave stains. A stained glass clerestory above would cast light upon the congregation, migrating across as the seasons changed. On some occasions, the central aisle would be perfectly light in rainbow light. A single split tile under one of the pews marked the solstice. Overall, it was a beautiful example of how architecture can be both inspiring and practical.

That church building was demolished in 2016 to make way for a new development. So it goes.

That promised development has still yet to develop and it remains a vacant lot to this day. https://maps.app.goo.gl/5F3eRVK9rm2VnKm6A

This is just one of many buildings that I have watched as they were designed, constructed, occupied, abandoned and destroyed. Friends are sometimes surprised at my ambivalence upon seeing old buildings demolished. You would think I would be more concerned about preservation but truthfully, I have learned that like everything we know, architecture is temporary. When you build a stone wall, you think to yourself, “That’s going to last forever,” but no matter how good your masonry skills are, someday it will fall and those fallen stones will turn to dust.

I’m not being nihilistic. My viewpoint is that architecture needs people, and without those people who take care of it, utilize it and rebuild it, the architecture will deteriorate and eventually blow away. So, when I see a lovely building being demolished, I don’t mourn the glass, concrete and stone. I grieve for the people who let the building die.

This early experience of watching the sanctuary be constructed along with my vast LEGO collection, inspired me to be an ARCHITECT.

Again, I was certain that I was going to be the next famous architect.

It was 1992, Lubbock, Texas. Progressive Architecture magazine was my bible. Texas Tech didn’t have as many trees back then, but I found it to be an inspiring yet bland, brick environment conducive to learning and fun. Architecture school was amazing, and I would go back in a heartbeat*. Especially with the fancy tools they have today. Architectural education in the mid-90s was almost indistinguishable from the previous fifty years. We still drafted with rapidograph pens on vellum using a parallel bar and learned to letter like proper architects. We knew CAD was the future, but it wasn’t quite the design tool it is today.

I was a wiz at model building and my delineation was above average (my own children have quickly surpassed me). I was enthralled by the romance of architecture school. I remember the late hours in the studio as being more fun than work. In my first year, I traveled with the college over spring break up to Chicago and back. We got to tour Bruce Goff’s Shin’enKan (Price House), a home that inspired me to have more fun with architecture. A few years later it burned to the ground. So it goes.

The first few years were a blur of school and experience. I experimented with architecture and with hair. I had more success with the architecture.

I worked as a cook and driver for Pizza Hut. I later worked as an assistant at the City of Lubbock Planning and Zoning Department. Job responsibilities included calculating the area of odd-shaped lots, preparing physical presentations for planning commission meetings, and running dozens of copies on an actual blueline machine located in a vault. The ammonia was sometimes overwhelming. I learned valuable skills at both jobs…more so at Pizza Hut.

In the second half of my third year, I met my life partner, Lori. When I graduated in 1997 with a Master of Architecture, we announced our engagement to our families. Her mother was quite concerned until I explained that we would wait another two years for Lori to graduate before we would set a wedding date. Unfortunately, this would mean living apart during that time. I moved to Houston alone.

For a third time, I was certain that I was going to be the next famous architect.

Do you have any idea how little an architect with a master’s degree got paid in 1997? I had a job offer for $28k a year in Dallas but my family was in Houston, and I knew that my good friend Chad had been offered more for the same job, he like runs that place now, btw. After numerous false hopes, I was finally offered a job at American Construction Investigations reviewing plans for compliance with the Texas Accessibility Standards, a relatively new State law based on the ADA. The job paid $10 an hour with no benefits, but I needed work and thought of it as just a temporary job. Each month, I would somehow manage to mail $100 back to Lubbock to help Lori out. It wasn’t much, but was a great way to remind her that I was waiting for her and loved her.

Two years later, she graduated, moved to Houston and immediately got an offer for more than I was currently making. We got married, bought a house in what is now a cool part of town but in 1999 it was considered to be dangerous, nicknamed Gunshot Heights.

I left ACI primarily to finish out my internship so that I could start the Architect Registration Exams (so much effort for such little money). By 2004, Lori and I had both become registered architects. We are probably the only architect couple that has sequential registration numbers. We were having fun raising our kids and renovating our house. I jumped between a few different jobs, even attempting to go solo at one point.

Instead of seeing booming success as a design architect, I got an offer to return to ACI in a management position. The money was good, and I began to remember the nice things about working at ACI. Since I became a registered architect, I no longer had that feeling that I was wasting time at a non-design firm. Management turned into ownership. Not bad for a guy that started at ten bucks an hour and wore a pager.

The job ultimately took me as far west as Hawaii and as far east as Riyadh. I have been to both Portlands, Key West, Los Angeles and most places in between. I have worked on amazing and mundane projects and none of them seem to be able to get their accessible toilets right.

In 2016, Lori and I moved to Meyerland, a neighborhood that was much better for our elementary and middle school daughters. We purchased a ranch style home that had been poorly flipped and worked our architecture magic on it. We added a two-story addition and fixed the floor plan. We had been in the house for less than a year when Harvey dumped 48” of rain and we flooded. The original portion of the house had about two feet of water. Fortunately, we had the elevated addition and sheltered there overnight with our neighbors, about 13 of us in total. All of our work on the renovation was a waste. So it goes.

We rebuilt and it’s really much nicer.

In September of 2020, I had just returned from a business trip and was walking hurriedly through IAH when I got a call from my partner’s eldest son. He told me that Henry was dead. In one moment, my mentor, friend and business partner, was gone. I owe so much to him. He taught me to be honest in work, generous to others and patient in everything. Most importantly, he wanted everyone to know how important it was that they take care of themselves. Although he was never known as a design architect, he was a great influence in the industry and respected by all.

Carrying forward his legacy, in 2024, I sold 90% of the company to my coworkers. This has been a real relief.

My children went off to school, one of them is even studying architecture. Woohoo!

Lori retired from architecture to open a distillery where I help out with mowing grass, brewing beer, wiring process controls, fretting over boilers, and yes…making pizzas. I have come full circle.

Now, I’m not so certain that I am ever going to be the next famous architect.

PS: If you ask me if you should go study architecture, my short answer is, YES! Just be ready for it to be something other than what you expect.

Jeromy, Brewer, Teller of Dad Jokes, Pizza Cook, Still an Architect,

September 2025 Newsletter Topics

When it comes to accessibility in employee work areas, the requirements are often misunderstood. The 2010 ADA Standards (Section 203.9) and Texas Accessibility Standards (TAS 203.9) are clear: each work area must provide an accessible route for entry and exit.

You’ll notice a new look in our September newsletter. To make the experience more visual and easier to navigate, we’ve separated our content into a featured story plus a set of shorter highlights.

But there’s more than meets the eye; instead of stopping at a quick blurb, each highlight now lives as a mini blog on our site. That means more detail, more takeaways, and a better resource for you.

This month’s highlights cover accessibility in employee work areas, lessons from fitness center design, and our monthly Project Spotlight.

Accessibility FYI: Work Areas Must Provide Entry and Exit

When it comes to accessibility in employee work areas, the requirements are often misunderstood. The 2010 ADA Standards (Section 203.9) and Texas Accessibility Standards (TAS 203.9) are clear: each work area must provide an accessible route for entry and exit.

That doesn’t mean the entire work area has to be fully accessible at all times. Instead, the rule focuses on three key points:

Approach: Employees with disabilities must be able to enter the work area.

Enter: The doorway and route into the space must meet clearance and maneuvering requirements.

Exit: There must be a safe, accessible way out in case of emergency.

Full maneuvering space inside the work area isn’t required, unless the space is large enough to accommodate it or unless fixed elements (like desks or equipment) are provided. This is a common point of confusion, but the distinction is important: the law ensures equal opportunity to work in the space, even if every workstation detail isn’t immediately adjustable.

The takeaway? Design with the future in mind. By providing accessible entry and exit routes, you create flexibility for employers to adapt the space as needed for any employee.

RAS Corner: Accessibility in Everyday Places – Fitness Centers

Fitness centers are a common amenity in multifamily housing, but they’re also a common place where accessibility can get overlooked.

The 2010 ADA Standards require that equipment and spaces in these rooms provide an accessible route. That means:

Clear floor space: At least 30” x 48” next to each type of exercise machine so a person using a wheelchair can approach and transfer.

Routes between equipment: At least 36” wide pathways that aren’t blocked by tightly packed machines.

Turning spaces: A 60” circle or T-shaped space so users can maneuver within the room.

When fitness machines are crammed too close together, these clearances disappear. The result? A room that looks appealing but is unusable to many residents.

The lesson is simple: design for movement, not just maximum equipment. By spacing machines appropriately and planning circulation, fitness centers become welcoming, functional, and code-compliant for everyone.

Project Spotlight: The HAY Center – A Campus for Belonging

In Houston, The HAY Center is redefining what it means to design with purpose. Created to serve youth aging out of foster care, the new campus combines housing, support services, and community amenities into one thoughtful development.

The project includes a 41,000-plus square foot residential building with 50 fully equipped apartments, each with a kitchen and washer/dryer, and some designed for young parents with children. A 17,000 square-foot support building houses life-skills classrooms, counseling offices, study areas, and a business center. The result feels more like a college campus than a housing complex, intentionally fostering both independence and a sense of belonging.

Accessibility was central to the vision. From clear routes and maneuvering spaces within units, to shared amenities like a fitness center and community kitchen, the design ensures residents can use every aspect of the campus. The youth themselves were involved in visioning sessions, ensuring the final product responded to real lived experiences.

The HAY Center shows how accessible, inclusive design can extend far beyond compliance. It creates opportunity, dignity, and community for those stepping into adulthood without a traditional safety net. Projects like this remind us that the built environment isn’t just about meeting codes — it’s about shaping futures.

Before It Becomes a Lawsuit: Why Proactive Accessibility Reviews Protect More Than Compliance

Most accessibility lawsuits do not start with bad design; they begin with minor, fixable oversights. A threshold that is a fraction too high. A ramp that flattens before the landing. A door clearance with just a little too much slope. These details may seem minor during construction, but they are often what trigger ADA lawsuits, Fair Housing complaints, and premises liability claims after occupancy. The common thread is that someone assumed compliance was covered. At ACI Consulting Architects, we help project teams catch these issues before they ever reach that point. Through Accessibility Reviews, Fair Housing Reviews, and Building Code Reviews, our proactive inspections protect timelines, budgets, and reputations.

How proactive accessibility reviews and inspections protect more than compliance.

Clarity Before Conflict

Most accessibility lawsuits do not start with bad design; they begin with minor, fixable oversights. A threshold that is a fraction too high. A ramp that flattens before the landing. A door clearance with just a little too much slope. These details may seem minor during construction, but they are often what trigger ADA lawsuits, Fair Housing complaints, and premises liability claims after occupancy. The common thread is that someone assumed compliance was covered. At ACI Consulting Architects, we help project teams catch these issues before they ever reach that point. Through Accessibility Reviews, Fair Housing Reviews, and Building Code Reviews, our proactive inspections protect timelines, budgets, and reputations.

Why "Close Enough" Is Not Compliance

Across the country, we see the same trend: teams focus on large-scale compliance, such as sprinklers, structure, and energy, while treating accessibility as a late checklist item. But accessibility standards found in the ADA, Fair Housing Act, and International Building Code (IBC) do not leave much room for interpretation. A landing that exceeds a 2 percent slope may drain well, but it no longer qualifies as a level maneuvering clearance. A door pair that meets the building code's width may still fail the ADA clear opening requirement. These minor discrepancies are what open the door to claims and enforcement actions. Accessibility is not about perfectionism; it is about precision.

The Value of Proactive Accessibility Inspections

Our approach begins long before ribbon-cutting or permit closeout. Proactive inspections during construction identify conditions that paper reviews can miss, such as site grading shifts, misaligned slopes, or improperly installed thresholds. Each review or inspection creates a clear record of compliance efforts. In the event of a complaint, that documentation becomes a robust defense, demonstrating due diligence under both federal accessibility laws and state-adopted building codes. These proactive reviews are not only about ADA and Fair Housing compliance; they are about protecting your investment from slip and fall risks, premise liability, and costly post-occupancy retrofits.

Adding Due Diligence Surveys to the Equation

Accessibility and code compliance do not end when a project opens, nor do they begin when drawings are stamped. Many of the calls we receive today come from developers and investors performing due diligence surveys before acquisition. These surveys identify accessibility, Fair Housing, and Building Code deficiencies that could affect property value, financing, or resale potential. A due diligence accessibility inspection can uncover items that may not stop a sale but could trigger significant post-closing obligations, such as barrier removal under the ADA or retrofit requirements under Fair Housing laws. When paired with a Building Code Review, this type of assessment provides a complete picture of compliance risk and capital planning needs. For investors, it is a small investment that prevents surprises and strengthens negotiating position before closing day.

Navigating State and Federal Requirements

Accessibility enforcement varies from state to state, but the fundamentals remain consistent.

In Texas, for example, Registered Accessibility Specialists (RAS) conduct reviews and inspections under the Texas Accessibility Standards (TAS), which are aligned with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

Other states rely on local code officials or third-party consultants to verify compliance with the International Building Code and ANSI A117.1.

ACI's consultants work across both models. We perform TAS Reviews and TAS Inspections for Texas-based projects while providing ADA, Fair Housing, and Building Code Reviews nationwide. That dual expertise allows us to help architects, owners, and contractors reconcile differences between the ADA, Fair Housing Act, and International Code Council (ICC) standards, ensuring each project is defensible no matter the jurisdiction.

When Accessibility and Fair Housing Intersect

In mixed-use and multifamily developments, accessibility responsibilities often overlap. Leasing offices and amenities typically fall under the ADA, while dwelling units and shared spaces trigger the Fair Housing Act's design and construction requirements. Our Fair Housing Reviews and Fair Housing Inspections clarify those boundaries early. We identify which areas fall under each standard and flag potential conflicts, such as thresholds that pass ADA but fail FHA maneuverability or unit kitchens that lack proper clear floor space. Coordinating accessibility and Fair Housing compliance before construction is one of the most effective ways to prevent rework and defend against housing discrimination complaints later.

Beyond Accessibility: The Role of Code Reviews

Accessibility is just one piece of the compliance puzzle. Many accessibility issues originate in the Building Code itself, where occupancy, fire separation, plumbing fixture counts, and egress requirements overlap with accessible design criteria. Our Building Code Review process integrates accessibility at every step, ensuring alignment between ADA, IBC, and local code amendments. Whether a project is seeking a building permit, addressing plan review comments, or preparing for final inspection, we make sure accessibility requirements are embedded in the broader compliance strategy. This integrated approach not only reduces project risk but also improves coordination among architects, contractors, and owners, helping ensure that "compliant on paper" truly means compliant on site.

Documentation Is Your Best Defense

When disputes arise, documentation often determines the outcome. Our reports provide detailed references to applicable standards, annotated plan markups, and photo records that can support design intent, field conditions, or corrective actions. This record keeping has proven invaluable in Expert Witness and Premise Liability cases involving ADA, Fair Housing, and Slip and Fall claims. Whether defending an architect, owner, or property manager, a well-documented review or inspection can demonstrate diligence, mitigate exposure, and protect professional reputation.

Why Proactive Matters

By the time an accessibility issue becomes a lawsuit, it is no longer about compliance; it is about perception. An early investment in a TAS Review, Fair Housing Review, or Building Code Review is far less costly than legal fees, schedule delays, and public scrutiny. Accessibility is not only a legal requirement; it is a reflection of professional integrity. Whether your project is in Texas or beyond, proactive accessibility inspections and reviews ensure your buildings are not only compliant but defensible, usable, and equitable.

Protecting Projects Before Problems Arise

Whether you are designing, building, or acquiring a property, now is the time to get ahead of potential compliance risks. ACI’s team of Registered Accessibility Specialists, architects, and code consultants provides proactive Building Code Reviews, Fair Housing Inspections, Accessibility Reviews, and Due Diligence Surveys that identify issues before they become liabilities. Our goal is to keep your projects defensible, accessible, and fully documented — protecting both your investment and your reputation. When it comes to accessibility and code compliance, the best defense is prevention.

October 2025 Newsletter Topics

It is one of those subtle construction adjustments that can turn into a compliance issue down the line. We often see it when a contractor tries to "make up" the difference between sidewalk elevation and finish floor elevation by slightly tilting the concrete pad at an entry. The goal is to create a smooth transition, but in doing so the slope often creeps past the 2% limit, pushing the landing out of compliance. The result can be a perfectly poured but perfectly noncompliant maneuvering area. The fix is simple: verify grades early. It is always easier to form a flat surface than to grind one back into compliance later.

🔷 Accessibility FYI: Door Clearances & the 2% Rule

It is one of those subtle construction adjustments that can turn into a compliance issue down the line. We often see it when a contractor tries to "make up" the difference between sidewalk elevation and finish floor elevation by slightly tilting the concrete pad at an entry. The goal is to create a smooth transition, but in doing so the slope often creeps past the 2% limit, pushing the landing out of compliance. The result can be a perfectly poured but perfectly noncompliant maneuvering area. The fix is simple: verify grades early. It is always easier to form a flat surface than to grind one back into compliance later.

🔷 RAS Corner: The Unexpected Hazards of Inspections

Some site hazards are obvious, such as open trenches, fresh paint, or the occasional forklift in reverse. Others are six pounds of fury wearing a collar. During a recent inspection, one of our RAS team members was met by a Chihuahua guarding a sidewalk like it was Fort Knox. We have faced all kinds of challenges in the field, but few have matched the tenacity of that tiny four-legged gatekeeper. Encounters like these remind us that fieldwork is not just about technical accuracy; it is about adaptability, patience, and knowing when to let the little dog win.

🔷 Project Highlight: Kids’ Meals Office and Warehouse

Every once in a while, a project reminds us that accessibility is more than a code requirement; it is a bridge to community impact. The new Kids’ Meals Office and Warehouse in Houston supports an incredible mission: ending childhood hunger by delivering free, healthy meals to the doorsteps of Greater Houston’s hungriest preschool-aged children and, through collaboration, providing their families with resources to help end the cycle of poverty.

ACI provided TAS plan review and inspection for this two-story tilt-up concrete and steel structure, which houses a café, training rooms, offices, and a high-pile storage warehouse for meal preparation and distribution. Ensuring clear routes, compliant entries, and accessible service areas means this facility is not only efficient but also welcoming and inclusive to all who serve, visit, and benefit from its work.

When Vehicles Invade the Sidewalk: Understanding Clear Width Requirements and Overhang Hazards

One of the most common—and often overlooked—barriers to accessible design is the encroachment of parked vehicles, particularly overhangs, into pedestrian routes. While a sidewalk may appear compliant based on its poured dimensions, actual usability can be compromised once vehicles are parked, especially head-in.

In the world of accessibility compliance, a few inches can make all the difference. One of the most common—and often overlooked—barriers to accessible design is the encroachment of parked vehicles, particularly overhangs, into pedestrian routes. While a sidewalk may appear compliant based on its poured dimensions, actual usability can be compromised once vehicles are parked, especially head-in.

This post explores clear width requirements, the impact of vehicle overhangs, and why good intentions on paper can result in noncompliance once a site is occupied.

What Is Clear Width?

Under both the 2010 ADA Standards for Accessible Design and the Texas Accessibility Standards (TAS), the minimum clear width of an accessible route is 36 inches (915 mm), as established in Section 403.5.1 of both standards. This minimum must be maintained continuously, excluding allowable reductions under the exception to 403.5.1, which permits a reduction to 32 inches (815 mm) for a maximum length of 24 inches (610 mm), such as when passing a door jamb or a short, fixed obstruction.

However, where an accessible route also serves as a general pedestrian walkway—especially in multifamily or mixed-use developments—the layout must also anticipate and prevent routine encroachments by vehicle overhangs, landscaping, or site furnishings.

Where passing spaces are required (typically every 200 feet where the route is less than 60 inches wide), Section 403.5.3 requires a passing space at least 60 inches by 60 inches (1525 mm x 1525 mm).

A sidewalk designed with a gravel buffer appears compliant until a parked vehicle’s trailer hitch reduces the clear width to just 24 inches—well below ADA and TAS requirements.

The Real-World Problem: Overhang Encroachment

The images included here illustrate sidewalks that appear compliant based on their constructed width yet are rendered unusable when parked vehicles encroach into the pedestrian path. In one example, a trailer hitch reduces the sidewalk to just 24 inches of clearance. In another, a flatbed truck has been backed into a head-in space, with the bed extending far enough to completely block pedestrian access. This is a dramatic but instructive example—not of a design flaw, but of how actual parking behavior and vehicle type can create unanticipated barriers.

A trailer hitch from a parked truck encroaches into the sidewalk, reducing the clear width and creating a barrier for pedestrians with disabilities.

A flatbed truck backed into a space entirely blocks the sidewalk. While designers are not required to account for commercial vehicle overhangs, this condition highlights the unpredictability of parking behavior.

While code does not require designers to anticipate commercial vehicles or flatbeds in standard parking spaces, such real-world conditions reinforce the importance of designing for at least a 24-inch overhang buffer. Sidewalks built to the 60-inch minimum are compliant but may still be impacted when vehicles pull forward—or in rare cases, back in—and intrude upon the pedestrian route.

These conditions are especially concerning for individuals using wheelchairs, scooters, walkers, or strollers who may be forced into vehicular traffic or otherwise unsafe conditions.

Why Vehicle Overhangs Matter

The typical passenger vehicle can extend 24 to 30 inches past the front wheels, and trucks or SUVs with towing hitches or cargo racks can protrude even more. In the absence of a physical deterrent (e.g., wheel stops or landscaping), many drivers will pull all the way forward, causing their vehicle to invade the sidewalk.

This behavior reduces the available clear width and can bring the sidewalk out of compliance with Section 403.5.1. While the exception to 403.5.1 allows for a temporary reduction in width due to fixed obstructions, vehicle overhangs are not fixed or permanent and therefore do not qualify.

Additionally, Section 502.7 of both the TAS and ADA requires that access aisles for accessible parking spaces be located so they are not obstructed by parked vehicles. While this section does not address truck overhangs directly, it reinforces the general principle that sidewalks and accessible routes must remain clear of vehicular encroachment.

Clarifying the Role of Sidewalk Width

A sidewalk built to 60 inches wide is considered sufficient to meet minimum accessibility requirements and allows for passing space without requiring periodic widened areas. That said, designers may wish to go beyond this minimum in locations where frequent truck use or trailer hitches are likely.

Designing for an assumed 24-inch vehicle overhang is a common risk mitigation approach. While not required, incorporating a buffer zone between parking spaces and sidewalks can help ensure the full clear width remains usable.

Relevant Standards and References

TAS / ADA 403.5.1: Requires 36 inches minimum clear width along accessible routes.

TAS / ADA 403.5.1, Exception: Allows reduction to 32 inches for up to 24 inches in length, only for fixed obstructions.

TAS / ADA 403.5.3: Requires a passing space of 60 inches at intervals of 200 feet where the accessible route is less than 60 inches wide.

TAS / ADA 502.7: Requires that access aisles be located to prevent obstruction by parked vehicles.

Mitigation Strategies and Best Practices

To prevent vehicle overhangs and ensure accessibility, consider these strategies:

Install Wheel Stops: Use concrete wheel stops to prevent vehicle overhang from encroaching into the accessible route.

Add Landscaping Buffers: A gravel strip, planting bed, or curb detail between parking and walkways creates a natural barrier to encroachment.

Widen the Sidewalk When Feasible: While not required, sidewalks wider than 60” may help mitigate overhang impact in areas with expected truck traffic.

Use Parallel Parking Where Appropriate: Eliminates forward overhangs altogether.

Conduct On-Site Inspections Post-Occupancy: Verify that as-built conditions and user behavior still meet accessibility goals.

A sidewalk with wheel stops installed to prevent vehicle overhangs, ensuring the clear width remains accessible for all users.

Real-World Risk: Compliance vs. Usability

The question isn’t just whether the sidewalk meets code at occupancy — it’s whether it functions as intended once residents, guests, and commercial vehicles begin using the site. The gap between design and daily use is where accessibility barriers emerge—and where plaintiff-side testers often identify ADA/FHA violations.

ACI’s Approach

At ACI, our team of registered accessibility specialists prioritize both compliance and real-world usability. Our team has reviewed thousands of projects where technically compliant sidewalks failed due to predictable site conditions like truck overhangs. We work with developers, architects, and attorneys to evaluate and mitigate these issues early, on paper and in the field.

Conclusion

Sidewalks meeting the 60-inch minimum are considered compliant, but actual use conditions may demand more thoughtful design. While not required to anticipate commercial vehicle encroachment in every case, designers should account for standard passenger vehicle behavior and consider a 24-inch overhang buffer in layout decisions.

Accessibility isn’t just about minimums—it’s about outcomes.

ACI provides nationwide accessibility consulting for ADA, Fair Housing, and TAS compliance.

Contact us to schedule a review or inspection, or to learn how we can help you incorporate accessibility into your project—on paper and on site.

Disclaimer: This post is for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal or regulatory advice. Code interpretations may vary by jurisdiction and project. Always consult a Registered Accessibility Specialist (RAS), certified code official, or legal counsel familiar with the applicable standards in your area before making design or compliance decisions.